Something got into Tacoma’s way of thinking about 1910 and for the next two decades the City changed in extraordinary ways. It was the progressive era in the Pacific Northwest where women’s suffrage, trust busting and political mechanisms like initiatives, referendums and recall were all adopted and embraced. But Tacoma went much further in a frenzie over collectivism, self investment and big ideas. The City saw itself as an early day Bitcoin and the speculative spirit of its population was all in.

When the City of Tacoma built it’s own hydroelectric dam at LaGrand on the Nisqually River in 1910-12 it was one of the first public owned power projects in the country and cost citizens more than $58,000 ($2.3m in 2024). In 1917 voters approved another big ticket idea, a bond issue to purchase 70,000 acres for $2, 000,000 and then gift it to the U.S. Army for a military base at Fort Lewis. The next year, 1918, they voted to create a publicly funded Port of Tacoma on 240 acres after previously building a new 11th Street lift bridge (Murray Morgan Bridge) to get there.

Chester Thorne, a lawyer and big city booster seemed to be behind most of the campaigns, becoming the first president of the Port Commission and a key figure in a 1923 civic charge to replace the aging Tacoma Hotel. By 1925, Tacoma investors had bought enough shares to build the new downtown Winthrop Hotel and its four story parking garage. And then, for the most adventurous Tacoma investors, Thorne and millionaire arctic explorer James Ashton, launched a moonshot enterprise-a motion picture production company. It was called H.C. Weaver Productions and by 1925, shares had been sold (at $10 per), capital raised, real estate acquired and a massive sound stage and movie colony built at Titlow Beach. The dream of Tacoma becoming a sort of Hollywood in the Pacific Northwest was worth buying into for some, but for many others it was a preposterous notion that was going nowhere.

The skeptics were silenced in May when the the Tacoma News Tribune splashed across its front page a montage of glamor photos of big Hollywood stars who were headed to Tacoma to make a movie called Hearts and Fists. The big stars were John Bowers, who would play the leading character in a story about a troubled lumber camp, and Marguerite de la Motte, his plucky and determined love interest. The villian was played by Alan Hale, who would later be the bad guy, Captain Bullwinkle, in Tugboat Annie Sails Again, which premiered at Tacoma’s Pantages in 1940. His lookalike son, Alan Hale Jr., was the Skipper on the television comedy Gilligan’s Island.

But Bowers and de la Motte were the big stars. He was a dashing veteran movie star who appeared in more than 90 Hollywood films beginning in 1914. By the mid 20’s Bowers was an A-list action star doing his own stunts in westerns, period adventures and romantic costume dramas while living life large off screen in his Hollywood mansion with a 1924 Duesenberg in his garage full of race cars, a sailing yacht and his own racing airplane called “Thunderbird”. Marguarite was a former dancer and rising star when she was cast opposite Bowers in the 1923 film Desire. They were married the following year and would go on to make a dozen films together during a highly publicized relationship that was at its peak when they arrived at Union Station with press cameras flashing and fans waving for autographs.

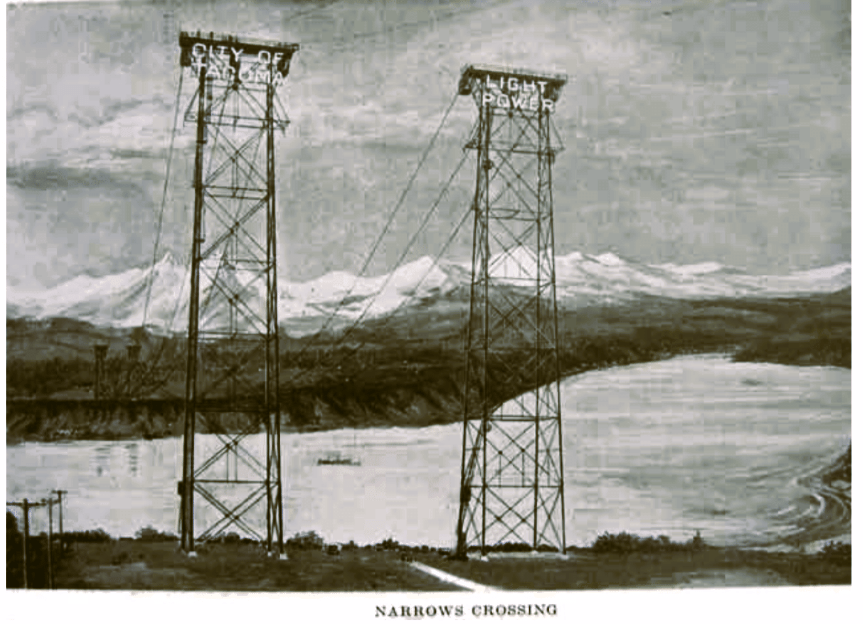

Shooting on Hearts and Fists began on May 11th, 1925 and over the next few weeks scenes were filmed at the Titlow Beach studio, at the Clear Fir Lumber Company sawmill on nearby Day Island and in the timberlands around Lake Kapowsin and Eatonville. By late summer the film was in editing while Bowers and de la Motte went on to each make more than 10 films in the next two years. From the location shooting on Day Island, the stars could have seen work beginning on one of Tacoma’s most audacious public works projects-the spanning of the Tacoma Narrows with transmission lines to carry power from the new Cushman Hydroelectric dam more than 60 miles away. At the time, the longest cable span in the world was just over 5000 feet between anchor points over land. The engineers on the Tacoma project intended to build steel towers on each side of the narrows and run six transmission cables over a mile in between and do it over salt water.

John Bowers returned to Weaver Studios the next year, in May 1926 to star in Weaver Studio’s third feature, Heart of the Yukon, with co-star Anne Cornwall. Director W. C. Van Dyke had worked with the actress in the studio’s second film, Eyes of the Totem earlier that year. Ms. de la Motte joined her husband in Tacoma during the filming but was not in the cast. The couple were once again a sensation in the city, occupying a grand suite at the Winthrop Hotel, attending banquets as guests of honor and maybe enjoying Tacoma’s lax prohibition era liquor laws a bit too much.

In a very theatrical way, the movie star celebrities were upstaged by the country’s most famous figure, just as filming was being moved from locations on the Mountain to the Weaver studios at Titlow Beach. On May 24th, President Calvin Coolidge pressed a telegraph key in Washington D.C. signaling the flow of power from Cushman Dam over the Narrows transmission lines and into the city of Tacoma. The surge of affordable public power helped accelerate a real estate boom just as Tacoma’s population passed 100,000 and automobiles made it practical to build homes outside the city’s tight steetcar network. The Cushman power project along with the construction of the College of Puget Sound and the launch of ferry service at the foot of 6th Avenue pushed the city west and all-electric brick veneered bungalows began characterizing whole new neighborhoods. Tacoma’s city limits became fixed much as they are today during the 1920’s as newly incorporated municipalities like Fircrest ringed the city on the edges that were not saltwater shoreline. By the middle of the decade hand made wood frame housing filled nearly 7000 of Tacoma’s 8000 residental blocks. Driveways and front facing garages became part of the residental streetscape, sidewalks and street trees became optional and streetlighting moved to motorcar arterials like 21st and 6th Avenue.

The Heart of the Yukon wrapped shooting in mid June and John Bowers headed back to Hollywood with his wife and a long list of films ahead. 1927 was a busy year for both headliners including Ragtime, a film they made together, but Hollywood’s dream machine was slowing down as the novelty of sound and talkies were beginning to change the scene. The new technology was also stalling plans for the fourth Weaver Studio’s film called Big Run, another action piece set at a Northwest salmon cannery. In 1929 Bowers was cast in Al Jolson’s first full sound movie, Say It With Songs, after launching the talkie era with The Jazz Singer in 1927. The Warner Brothers film was written by Darryl F. Zanuck and was a major Hollywood production but Bowers at 45, found himself cast as an aging doctor rather than a dashing co-star. Meanwhile Marguerite, still in her twenties, was choosen to play the romatic lead in The Iron Mask with swashbuckling Douglas Fairbanks, who along with his wife Mary Pickford were among the most influencial people in the industry. Their careers seemed to be going in different directions just as silent films were fading to black and talkies were moving to center stage.

Back at Titlow Beach, Weaver Productions was shuttered and prospects for converting the big studio into a soundstage for talkies were growing dim. The property was put up for sale and Weaver Productions stock was back on the market and being snapped up by real estate speculators. Across the railroad tracks from the ferry dock the old Hotel Hesperides property was acquired for a public park and residental subdivisions above the beach were promoted and sold as Hollywood by the Sea. In 1932, the giant studio building was reopened as a dance hall and H.C. Weaver Productions formally dissolved as a corporation. Then on a warm night in August two shadowy figures were spotted leaving the hulking studio just as flames began climbing up the outside walls. By morning it was a total loss.

John Bowers, who hoped to star in the fourth Tacoma silent film, never made another movie after 1931. Like Weaver Productions he bacame a casuality of sound and the sudden end of the silent film era. He separated from Marguerite and burned through his wealth and celebrity during the early years of the Great Depression. After a desperate last call to director and old friend Henry Hathaway asking for a movie part Bowers drownded himself off Malibu Beach in November 1936.

Then, in 1937, Hollywood released a film that seemed to tell its own story about how the silent film era ended and at what cost in creative terms. The film was called A Star is Born and its tragic central character was a fading actor named Norman Maine played by Fredric March. The film was a critical and box office success and won the Academy Award for Best Original Story but among industry insiders its Malibu beach ending left little doubt about who’s story was told. It’s widely accepted that John Bowers was the inspiration for the character of Norman Maine, a silent star in reality and fiction there at Hollywood by the sea.

Thanks to Mick Flaaen for the idea behind this story, and Peter Blecha and HistoryLink for the backup…