“Tacoma has a history of getting into relatively bitter fights over matters of passing concern.”

Murray Morgan

Recap Part 1

Recap Part 1

By the end of the 1970’s, most of the commercial neon signage in Tacoma was vanishing. Federal Model Cities program design standards and local ordinances that discouraged or outlawed business signage over public sidewalks and right of ways were forcing merchants and small business people to remove classic neon box signs. It became an expensive and irritating tension between City Hall and the small merchants and business districts south and west of the downtown. And then in early 1980’s, just as the issue was residing and civic pride and unity seemed to be rebuilding around the dazzling new Tacoma Dome, an announcement was made about a major high priced, high brow artwork for the Tacoma Dome…

The bitterest fighting in Tacoma’s neon wars started in February 1984 when the City Council finalized the decision to spend a quarter of a million dollars from the construction of the Tacoma Dome on a watered down version of Stephen Antonakos’s artwork “Neons for the Tacoma Dome”. Almost two years prior, Tacoma’s approach to selecting the dome artwork was to hire a jury with major art world credentials (including Post Modern architect Michael Graves who had just completed the radical and controversial Portland City Hall Building). It may not have been a promising start and was certainly not the best way to engage the locals.

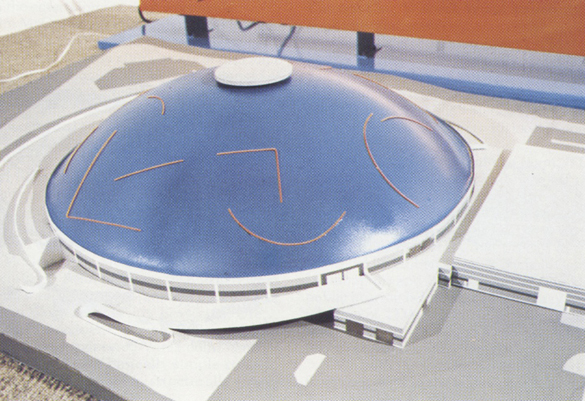

After due deliberation and a recommendation that the artwork be outside, the three person panel invited six artists from more than 50 submissions to prepare full design proposals. Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg were among the invitees that chose not to proceed but Andy Warhol, Richard Haas, George Segal and Stephen Antonakos delivered fully developed designs and models by March of 1982 and they were displayed around town. Three of the four designs used the massive dome roof as a canvas while only Segal went for an interior sculpture of trapeze artists hanging above the entrance. Warhol covered the dome in a giant brightly colored flower, Haas went for a painted night sky with hundreds of tiny lights for stars and Antonakos went neon large with a completely royal blue roof laced with glowing pink neon tubes that wormed inside the roof in 600 places. Distant scuffling could be heard as the choice moved to the arts panel for a decision.

In the meantime, Mayor Doug Sutherland, members from the Tacoma Arts Commission and Tacoma Dome jury, a downtown businessman and three others were added to the process as a citizens committee. The Tacoma Athletic Commission, including local sports hero Stan Naccarato and neighborhood groups who worked on passing the minidome bond issue were not included. Then, just days before the decision was due, the Dome architects released a technical report that questioned whether any of the three rooftop proposals could be executed without making the roof leak. Jimmy Zarelli, the general contractor that was building the dome went right to the local paper and stated he would withdraw his guarantee on the roof if any of the artworks were installed. When the panel convened on April 17th, 1982 Graves didn’t show up and the other two were furious with the architects (particularly lead designer Lynn Messenger who had submitted his own unsuccessful “big blue diamonds”design for the artwork). Then the chaos that so often precedes battle ensued.

First the two person professional jury blew off the design/build cautions and selected the Antonakos design. As agreed to in advance, the decision went to the Arts Commission, Citizen Advisory Group and the Dome jury with all concurring in the choice. The design build team fired back with a letter to the City Manager assailing the neon in both technical and aesthetic terms. The lines were drawn with the sports community siding with the dome builders and neighborhoods under the no-neon flag while the arts community, City Hall establishment and downtown businesses dug in on the other, more illuminated side. Five days later the City Council voted five to four to reject the Antonakos roof sculpture citing concerns that there would be no guarantee from the builders that the roof wouldn’t leak. The vote curiously restated the Council’s commitment to the one percent arts project for the Dome and dismissed the three unselected artists leaving the neon floating in a state of civic limbo. When the Tacoma Dome was completed a year later in April 1983, the architect’s blue diamond pattern covered the roof and the roof leaked.

jury with all concurring in the choice. The design build team fired back with a letter to the City Manager assailing the neon in both technical and aesthetic terms. The lines were drawn with the sports community siding with the dome builders and neighborhoods under the no-neon flag while the arts community, City Hall establishment and downtown businesses dug in on the other, more illuminated side. Five days later the City Council voted five to four to reject the Antonakos roof sculpture citing concerns that there would be no guarantee from the builders that the roof wouldn’t leak. The vote curiously restated the Council’s commitment to the one percent arts project for the Dome and dismissed the three unselected artists leaving the neon floating in a state of civic limbo. When the Tacoma Dome was completed a year later in April 1983, the architect’s blue diamond pattern covered the roof and the roof leaked.

So all of the early skirmishes of the building years were still festering when Stephen Antonakos reappeared before the City Council that February 21, 1984 with a new version of Neon for the Tacoma Dome, this time for the interior. His new plan involved two 12 foot high 100 foot long panels with multicolored neon in “energetic jumbles of squares, circles, squiggles, half archs and other geometric shapes”. At the recommendation of the Arts Commission, the Council voted 8 to 1 to award Antonakos a contract for $272,000 to create and install the neon artwork. The flanking actions of the early days were over and the No Neon in the Dome Committee led a full frontal change on City Hall.

First the No-Neoners turned three City Councilmen against their own votes and tried to block the signing of the contract but on March 15th they were outvoted at a raucous, fiery City Council meeting. Then the No Neon forces launched a petition drive to gather the 4200 signatures needed to put a neon referendum on the September ballot. By mid May the group had collected over 8000 signatures and Charlotte Naccarato had filed a Superior Court lawsuit to block installation of the neon on the grounds that the selection process was illegal. In a counter assault, the neon forces pushed Antonakos to finish the artwork and every effort was made to install wiring and mounting supports even before the actual neon was fabricated. Two days after the City Council set the date of September 18th for the neon referendum Judge Waldo Stone denied the lawsuit. Heavy casualties on both sides and the bloodletting had just begun.

The counter offensive by the pro neon forces took advantage of the fact that Antonakos had moved up his neon unveiling ceremony to July 31, several weeks before the referendum vote. They began spreading buttons, brochures and posters celebrating the important public artwork and in social circles and debates began references to the uninformed, uneducated opposition. Antonakos added his own unfortunate comment that his critics “were not enlightened in the world of art.” At the unveiling party, complete with lasers and champagne, Mayor Sutherland declared the controversy over and the artwork in place for all to enjoy. “Tacomans should stop bickering about how it got there” he remarked. Six weeks later 25,000 of Tacoma’s 80,000 registered voters went to the polls in the advisory referendum and neon lost by 70%.

The heat of the battle went back to City Council. As if the problem of dealing with a very expensive City asset that citizens seemed to want gone was not complicated enough, Seattle Mayor Charles Royer sent a public letter offering to purchase it if Tacoma didn’t want it. The letter may well have been sent as a favor to Mayor Sutherland but it made headline news in both cities and stoked the flames of tension between the neon factions. In a risky dodge, the Council decided to hold a massive public meeting at the Dome where people could testify on how to dispose of the neon and even cast ballots again on the various options. The December public meeting enraged the no-neoners who felt the issue had been settled. From within their numbers, several jihadists turned to Tacoma’s nuclear solution-a recall drive against the Mayor and Councilmen Pete Rassmussen and Jack Warnick two steadfast neon supporters.

For the first time in the neon wars, a deep wound in Tacoma’s history was opened and not-yet-healed tensions between economic classes and distinct neighborhoods reappeared. In 1968, Tacoma attempted the difficult feat of political suicide in self defense when it recalled the Mayor and a majority of the City Council all at one time. The election results created the impossibility of seating a quorum and consequently the inability to make decisions or conduct city business. In reflection, the targets of the recall deserved what they got but Tacoma’s North and South ends were sharply polarized over the vote and the resentments were still there in the 1980’s. Jack Warnick, in particular was a veteran of the 1968 recall and there were those on the No Neon side that remembered his involvement with no fondness at all. The neon recall did not enjoy the same success as the 1968 overthrow.

HISTORICAL DIGRESSION

Former Mayor Bill Baarsma tells a story about wondering at the time whether any good sized city in America had ever voted to recall a majority of its political leaders and thereby render itself unable to legally operate. It seemed so entirely irrational and crazy. So being a political science professor he began doing research. lo and behold he found another example from 1910. Yup, it was Tacoma who recalled Mayor Fawcett and the majority of the City Commission. Near death experience accomplished twice!

More than 600 people showed up at the dome under the neon for the hearing. It went as expected with both sides making their well worn arguments and a few extremists from each side hurling insults and political threats. No one left satisfied and in the months that followed the actions of the City Council reflected the tone of the event. The ballots cast on December 6 1983 were a mirror image of the September vote, counting just under 70% for the neon and offering no clarity at all about what to do next. But with the neon in place, polices about covering it up or turning it off for some events and leaving it on for others satisfied almost no one. During heated arguments at the City Council, actions were taken to tweak the Percent for the Arts ordinance so the no neon supporters turned their guns on the ordinance itself. In September 1985 Tacoma voters repealed the public art program, the last serious casualty of the neon wars.

Almost a decade passed and for the most part, the neon in the Tacoma Dome dimmed away from the controversy and hard feelings it once sparked. Then in the spring of 1993, Tacoma artist Dale Chihuly began to talk openly about neon and art at the Tacoma Dome again. Improbably, Chihuly proposed to use the hockey rink as a frozen platform for the installation of 100,000 pounds of geometrically formed ice encasing colored neon tubes. It was a marriage of materials and visual effects he had experimented with before but for the Tacoma Dome he was scaling up the undeniably neon installation to fit the home venue. It was also a wry, affectionate way of suggesting that Murray Morgan’s observation about Tacoma getting into bitter fight over matters of passing concern was right. The preparations for 100,000 Pounds of Ice and Neon involved hundred of people and weeks of advance work for an experience that would melt away in three or four summer days. Probably no one who saw the visually fascinating exhibit or enjoyed the cool icy neon light of the dome that day was thinking about metaphors but something very elemental was happening.

100,000 Pounds of Ice and Neon was

free to all and on the very warm late summer day it opened with a line of people winding up the hill and over I-5 from the Dome. Chihuly was informed that there were some technical issues with the electrical current and they would be delaying the opening past the promised 10 a.m. so he decided to go out and walk the line of people waiting to get in. Dale seemed to know everyone and just up the hill, not far from the front of the line he met an old friend. It was Stan Naccarato. They laughed and shared a moment of mutually recognized irony and then each moved on.

Some say Tacoma will never forget or forgive the Dome art controversy but if there was an Appomattox at the end of the neon wars, it was on that hillside outside the dome in September 1993.

I was a child when I first attended an event in the Tacoma Dome. I don’t remember the event….but I DO remember seeing those neon panels! I had no idea of the backstory until reading this blog post today. Wow! Thank you.

LikeLike