On Wednesday, April 24,1929, 41 year-old Kay Yamamoto took the witness stand for one more round of questioning in a grueling trial that was more than a month old. The courtroom drama involved a legacy of property and trust but the politics and prejudices swirling around the case tested Tacoma’s most deeply seated ideas about hard work, loyalty and shared history.

Kay’s attorney, Wesley Lloyd, began the questioning by walking the father of five through his life story. Then, on cross examination by opposing attorney Maurice Langhorne, Kay traced back over the same autobiography under a “thundering assault” on his loyalties, motives and race.

Kichigoro (Kay) Yamamoto was Issei, born in 1888 near Uwajima on Japan’s Shikoku island. As a boy of just 14 he followed his uncle, Yokichi Nakanishi, across the Pacific by steamship to Tacoma in 1902. Kay recounted for the court, working in the household of Mrs. C.M. Lawrence on South I Street where he learned English, and then joining his uncle’s growing truck farm operation near Fife.

The jury was charmed by Kay’s story of meeting his uncle’s landlord, a burly towering Irishman who bellowed with laughter watching the boy try unsuccessfully to milk his first cow. The man was John McAleer, and over the next decade “uncle Nakanishi” helped him turn a 40 acre dairy farm into a prosperous 300 acre vegetable growing enterprise called West Side Gardens. As McAleer bought and then leased more land for the gardens, and as the Japanese workers and their families grew in number, he helped arrange a language school for the community and then a gymnasium which Kay described in familiar terms. Kay didn’t mention that in 1912 he won the Pacific Northwest wrestling championship in the 125 pound weight class or that McAleer was delighted at the young man’s accomplishment.

Kay went on to remember that John McAleer and his wife Margaret built a stylish 10- room Arts & Crafts home near the West Side Gardens in 1918, just as the war was ending. By then Kay was married to Masae and they had a growing family that would soon include two boys and three girls. The Japanese American community in Fife was counted at 1,306 people in the 1920 federal census and the workforce at West Side Gardens reached 40, not counting the truck drivers that carried more than $200,000 in produce each year to markets and restaurants across the Pacific Northwest.

But along with the growing field worker population and high quality vegetable production was an increasingly complicated political atmosphere. Issues of agricultural land use and property ownership became entangled in polarizing post-war politics at both the state and federal levels. Issei farmers like Kay and his uncle could not own land and even the terms of leases and sharecropping agreements were under increasing scrutiny by governments and political organizations. West Side Gardens was part of a patchwork of agricultural partnerships that were delicately created to contend with shifting land laws and permit Japanese, Italian and other immigrant farmers to work the fertile land in the Fife valley. The shift became an earthquake in 1920.

In his testimony on that spring day in 1929, Kay passed lightly over how his uncle Nakanishi was summoned to the federal courthouse in Tacoma on July 28, 1920 to answer questions from the influential U.S. Congressional Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. The Committee was chaired by Congressman Albert Johnson, the country’s most powerful figure on immigration policy, who was at the time convening the hearings in his own district. Kay simply stated that after the congressional hearing a decade earlier, his uncle’s West Side Garden’s went bankrupt due to changes in the law.

In fact, the Tacoma and Seattle congressional hearings in 1920 were monumental in signaling a series of unprecedented laws and policies that changed the lives of farmers like Kay forever. The record is unclear about whether or not Kay was in the federal courthouse during his uncle’s appearance before the House Committee, but the Tacoma Daily Ledger reported in detail on the testimony given that warm, windy summer day in 1920.

Chairman Albert Johnson opened the hearing by introducing the members present from the United States House of Representatives’ Committee on Immigration and Naturalization including John Raker of California, William Viale of Colorado, Isaac Siegel of New York, and John C. Box of Texas. Johnson was in very familiar surroundings having worked as a reporter and editor for the Tacoma News in publisher Sam Perkins’ building right across the street. After a stint at the Seattle Times and with Perkins financial help he became part owner and editor of the Daily Washingtonian in Hoquiam. In 1912 he ran successfully for congress from Washington’s 2nd District which in those day included Tacoma and Pierce County. And in 1919, after three terms as a minority member, he ascended to the chairmanship of the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization.

Representative Johnson explained to the full courtroom that the Committee was investigating conditions on the west coast related to the “Japanese question”. From vitriolic statements made by members of the sub-committee, newspaper editorials and previous hearings in Washington D.C., it was expected that the Committee was preparing dramatic changes to Federal laws on limiting immigration, constricting pathways to naturalization and even limiting citizenship rights for native born Americans of Japanese descent. Information gathering sessions were held up and down the west coast that summer but most observers knew that the coming policies were a forgone conclusion and the hearings were little more than a campaign swing.

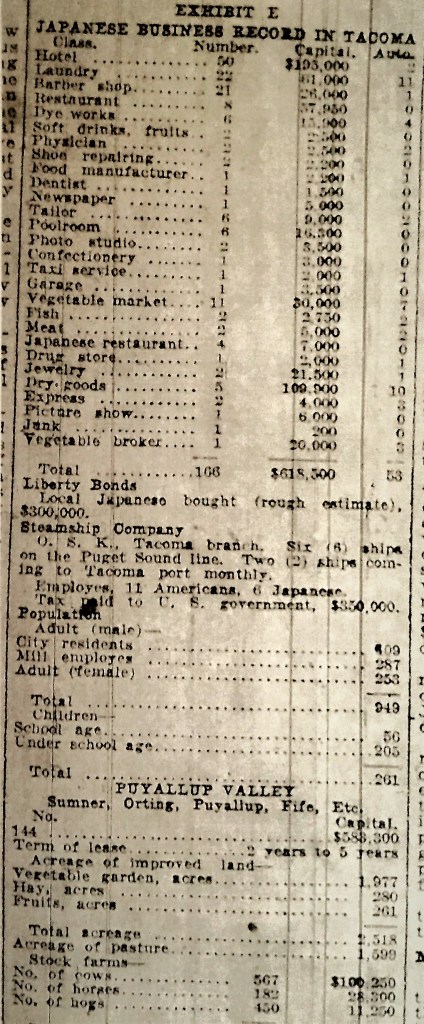

Under oath, the Committee heard testimony from M. Yoshida, Secretary of the Tacoma Japanese Association who presented a careful count of residents, businesses and industry in Tacoma and the Puyallup Valley. Kameji Nutahara, a pastor, S. Kuramoto, a farmer, and Miss Edith Moody, a health department statistician were questioned about birth certificates including several probing questions about whether the birth documents were provided to the Japanese government in order to receive dual citizenship for children. Ms. Moody and the others noted that the certificates were important to families because they documented citizenship for American- born kids but the questions about disloyalty from the congressmen made the unfounded suggestion part of the congressional record.

Some of the most unexpected testimony of the day came from Willis R. Lebo, a merchant in fish fertilizer and a keen observer of farming methods. Instead of just confirming the expanding acreage and production of Japanese operated vegetable and fruit farms in the Fife and Puyallup valley, he went on to express his admiration for the hard work and methods he was seeing. It was not what the committee wanted to hear but on the front page of the Ledger it became a headline. Mr. Lebo then offered:

“Mr. Nakanishi, of Fife is to my mind the dean of all agriculturalists. An intellectual in his own country, he is a scientific farmer who can grow three times as much as a white farmer on the same ground. He has taken a garden planted to cucumbers in rows five feet apart and planted lettuce between the rows, cleared $400 an acre from the lettuce and $600 an acre from the cucumbers. “The first use of tractors in the valley was on Nakanishi’s 269 acres…..”

And then, Chairman Johnson interrupted, admonishing Lebo to be careful in his statements. Unintentionally, Lebo had put uncle Nakanishi in the crosshairs of the unhappy committee and Nakanishi’s testimony was still to come.

Congressman Vaile aimed a question at Lebo. “Do you think it desirable that an alien race should occupy the farmlands of the country?”.

“I think it’s unfortunate that we should get patriotism and love of country mixed with business” Lebo replied. He noted that just two years earlier, as the Army was ramping up for war the farmers in Thurston County fell behind in providing Camp Lewis with vegetables. The Army went to West Side Gardens for help and Nakanishi responded by providing $1000 a day in fresh produce, delivered to the cantonment.

With the mood and tone heating up, chairman Johnson directed his own question at Lebo. “Which do you think is the greater man in the Puyallup Valley, Paulhamus or Nakanishi ?” It was a question that stunned the room for the unspoken implications it held.

Lebo answered, “Paulhamus holds a separate place. From the point of view of agriculture, Nakanishi is the greatest man on the Pacific Coast. I think the State could well afford to abandon its experimental station and hire one reporter to follow Nakanishi around his grounds to see how he eliminates plant pests, cultivates his soil and employs fertilizer and then writes it down. Instead of coming to see the Mountain (Mount Rainier), I think people should come here to see West Side Gardens.”

Congressman Raker from California made it clear he was offended by the last remark and its possible reference to the motor trip the Committee had made to the Mountain the day before. In fact, virtually everything Lebo had said was contrary to the Committee’s attitude and perspective, particularly the comparison between the operator of West Side Gardens and the singular figure referred to as “Paulhamus”. With Yokichi Nakanishi waiting in the gallery Chairman Johnson called him to the testimony table.

William Hall Paulhamus, former state senator, candidate for governor and founder of the Puyallup Fair was now the invisible character in the room as the political drama unfolded. What was unsaid but widely known was that Johnson and Paulhamus were close allies in their anti-Japanese ideas and beliefs. Less known but barely concealed was that they both were closely aligned, if not full-fledged members of the Ku Klux Klan.

It was under these circumstances that questioning began for Yokichi Nakanishi on the afternoon of July 28, 1920 in Tacoma.

A congressional hearing held in downtown Tacoma was big news in 1920. Not only because it was held in the the Federal Building immediately across the street from the newsrooms of the city’s two daily newspapers, but because it spotlighted a matter of divided opinion following America’s costly involvement in the First World War. The biggest political names in the national debate over immigration policy were on the dias in the crowded chambers on the third floor of the imposing stone building at 11th and A Street. After a full morning of witnesses and testimony, Yokichi Nakanishi was called before the committee for questioning.

The issei farmer, who had been praised for his industry and progressive agricultural methods by earlier witnesses, was asked to describe his vegetable growing enterprise, his legal partnerships and property agreements and the financial details of his West Side Gardens business. In reticent terms Nakanishi described his work as a cook, his adventures in Alaska and then his settling down to farming on land he leased from John McAleer and Henry Sicade. After years of failed crops due to flooding and frost damage he learned to understand the alluvial soil of the Fife Valley and now was cultivating 270 leased acres. He employed 35 to 40 Japanese workers and along with his nephew Kay Yamamoto was delivering produce as far away as Chicago.

Impatient with the farmer’s story, the Congressmen peppered him with questions about the terms of his rent and relationship with McAleer, about the taxes he paid and whether or not his children went to public school. It was a shopping list of the issues being addressed in the legislation the men were preparing. After the questions were respectfully answered, Mr. Nakanishi invited the committee to visit West Side Gardens. Chairmen Johnson replied that they would come to Fife the following Monday but the record is unclear as to whether they actually did.

If members of the congressional committee did visit the gardens, Kay Yamamoto and John McAleer were probably there and it’s hard to image Henry Sicade was not present. It would have been a fascinating occasion as it would have brought all of the major characters in this story together at the same time and place. In the minds of the congressmen, the group of men invested in the West Side Gardens were seen as the embodiment of the “Japanese problem.”

A wave of new laws began after the committee hearings that summer, first in the Washington State Legislature and then in the United States Congress. Early in the next state legislative session the famous and feverish House Bill 79 was passed January 27, 1921, adding to the state constitution alien land restrictions on not only ownership but affecting rent and leased properties. The language in Bill 79 criminalized selling or renting land to an alien or non-citizen but was openly directed at Japanese farmers and small business operators. It made it illegal to hold land in trust for an alien, something attorneys did for minor American– born children. The legislation even made it a crime not to report known violations of the law to the Washington State Attorney General or local prosecutors. The bill passed in the House by a vote of 71 to 19 and the Senate by 36 to 2. It took effect on June 9th, 1921, after planting but before harvest.

It was this Washington State legislation that broke the West Side Gardens. In order for it to continue, McAleer would have to return to full time farming or, as uncle Nakanishi suggested, he and Kay would give up their ownership interest and continue as employees. It was an indignity none of the men wanted or deserved but as historian Ron Magden wrote “At the highway gate the Irishman and the Japanese replaced Nakanishi’s West Side Gardens nameplate with a new sign, McAleer Gardens.” In the years that followed, the prolific gardens continued to supply greens, vegetables and flowers to the public markets, grocery stores and restaurants. Kay Yamamoto became the emissary of John McAleer in the daily operations of the gardens and as the old man and his wife’s household needs increased, the Yamamoto’s cared for them. In the last years of the decade, the McAleer’s began to put their affairs in order. John contacted his sister and nephews in Ireland about interest in the gardens and his American property but they were comfortable in their homeland and displayed no interest in immigrating. Margaret McAleer died in July 1927 and less than a year later, on May 3, 1928 John McAleer passed away. The Last Will and Testimony he left behind was reasonable and completely understandable to his friends and the people in the Fife farmlands but in the halls of Congress and the political offices in Olympia it was a bomb blast.

Riveting story Michael Sean Sullivan!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Soooo good!!

LikeLiked by 1 person